Abdul Ra’ouf was a 4 months old baby boy and he is another Lebanese tragedy. He was refused admission to hospitals in Akkar and has passed away. I suspect Abou Faour will hold a press conference soon.

-

-

May he rest in peace.

In late February, a scandal hit Hotel Dieu as the Ministry of Health, led by Abou Faour, froze its contract with that hospital over them not admitting a patient who had no other form of coverage.

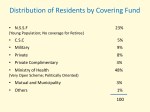

Heartbreaking stories of children dying make headlines, but they don’t tell you the truth of the health sector in Lebanon. That truth is in the numbers:

Before going into what thosee numbers mean, let’s take the hypothetical scenario of a hospital with 100 beds. The beds in that hospital are divided according to coverage: those covered by insurance have the biggest chunk allocated to them (let’s say 70), while those covered by NSSF have 20 beds and those covered by the Ministry of Health have the remaining 10.

Hold that thought for a second and let’s talk about the numbers.

Half of the Lebanese population (48%) is covered by the Ministry of Health (MOH), while 23% are covered by the NSSF (daman) and only 8% are covered by private insurance. This means that about 2 million Lebanese have the MOH as their ONLY way to afford hospital care in the country.

Having half of your people covered by the ministry doesn’t seem too bad right? The truth of the matter is far less utopian.

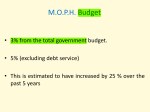

Having half the country covered by the MOH means those 48% are entirely dependent on the MOH’s budget. The disaster is when you find out that out of all the ministries running this country, the budget allocated for the MOH to cover the needs for HALF of the country is 3%.

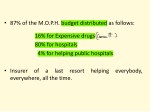

How The Ministry of Health’s Budget Is Divided:

16% that budget goes towards expensive drugs notably cancer treatment. Patients not covered by the NSSF have to resort to the ministry for their medication (if they can’t afford it, which is the case of 99.7% of Lebanese).

Getting the medication out of the MOH isn’t easy. Sometimes they run out of the medication and you end up having to wait until they bring it back into the country. Other times, as has happened with a friend of mine who needed a $12,000 treatment over the course of a couple of months, other people come in and take the medication that was allocated to you, sign for you and leave.

The system is rigged with wastas, bureaucracy and corruption.

80% goes to hospital care, which is where most of the people need the MOH: operations, hospital admission, etc.

So imagine ONLY having 80% of the country’s 3% budget used to essentially treat 50% of the Lebanese population. This is why the MOH has the least number of beds at the country’s major hospitals: the MOH often doesn’t pay, and when it pays, it does so extremely late.

So when you hear that a patient couldn’t find a bed at a particular hospital, it doesn’t always mean that every single bed in the hospital is full, it means that the beds for that patient’s coverage are fully occupied, and that is very easy to occur when 48% of the country gets a minimal amount of beds in the country’s major hospitals.

Does that sound harsh? Of course it does. All Lebanese are entitled to excellent care and that level of care is, sadly, rarely available outside of Beirut and its major hospitals. Why so? Because excellent care is not cheap. Those imaging equipment with fancy names you hear being thrown around on shows like House, MD and Grey’s Anatomy cost in the millions. Every time a hospital buys something to advance its level of care, they pay figures in the seven digits. Even the research that goes into advancing care is expensive.

The level of care being expensive is a big problem. The bigger problem is not having hospitals that are close to the level of those inside Beirut outside of the capital. Most of the people in the country cannot afford places like AUBMC, SGH or HDF, but they can go to public hospitals where the level of care has the potential to be excellent but is handicapped by how little funding those hospitals get.

4% of the MOH’s budget goes to help public hospitals. What you need to know is that public hospitals are not exactly under the jurisdiction of the MOH, which means that the Ministry isn’t responsible for their finances and how they run: they have a separate board of directors that is required to run them and keep them within profit margins. However, as is the case with almost all public hospitals in the country, very few (if not none) are success stories because of the lack of governmental support that goes toward them.

I rotated at one of those public hospitals not too long ago. It wasn’t an eye opening experience because I do come from a non-privileged area of the country, but it was a heartbreaking one. The hospital was in a state of near-decay. Some of the equipment didn’t work. And all the patients were one sad story after the next.

-

-

The state of the hallways.

-

-

Some of the doors.

-

-

The view is great though.

-

-

This is the elevator

-

The latest high profile example is Beirut’s Governmental Hospital which has been in the news for months now because of the lack of payment to employees. Imagine not getting your salary for months. Does it make it okay just because you’re a doctor or a nurse?

What Happens When The MOH Freezes Its Contract With A Hospital:

As a response to HDF not admitting the patient (who wasn’t a case of emergency in which case the hospital is required by law to take care of a patient), Abou Faour decided to put his ministry’s contract with the hospital on hold. I suppose he thought that was punishing the hospital enough, and you thought he was defending your rights in doing so.

What freezing that contract means is that those 10 beds in that hypothetical hospital are no longer allocated to patients covered by the MOH. Freezing a contract with a hospital affects the patients, not on the hospital.

Hospitals And Doctors Can Also Be Greedy:

There are a lot of hospitals and doctors in the country that are greedy, and the system permits the perpetuation of that greed.

The most relevant story to that regard is of someone I knew who required a major surgery. That person’s community tried to intervene by raising the funds. Eventually a high profile charity heard of that person’s problem and donated. In doing so, they forced the hospital in question to lower their required fees by a decent amount, because that charity needed the invoices to be audited abroad.

A lot of this goes on behind closed doors. The lack of regulations means that you don’t know which part of the money is going where.

The Media Doesn’t Help:

Out of all sectors in the country, medicine and healthcare are the juiciest to be spoken about in the media, and the way the media talks about hospitals and about patients dying is ignorant.

A couple of weeks ago, Marcel Ghanem shared a story on his show about a woman who died at a hospital in Jbeil because they didn’t give her some covers from the cold. People were outraged. Were those nurses seriously watching Yasmina and not giving the woman a blanket? What an atrocity!

The truth is very different.

That patient was a cancer patient. As a result of her chemotherapy (which she was able to afford!), her immunity was immensely suppressed, rendering her unable to defend against infection. The patient presented to the ER of that hospital with what we call “neutropenic fever,” which is fever in the background of immensely suppressed immunity. Why did the patient die? Because she ended up in septic shock, a condition with extremely high mortality.

But that doesn’t sound too media-appropriate. The problem with Lebanese media isn’t that they talk about stuff that go wrong in hospitals. They should, and they should do it more. It’s that the angle they often use is useless, leads to zero changes and doesn’t highlight the real problems here: inequality, lack of funding, lack of coverage, etc.

My Own Sensational Story:

She was such an adorable 4 year old when she walked into the doctor’s clinic in Beirut, coming all the way from Tripoli. What’s your name, we asked. Farah, she answered in a barely audible singsong voice.

Farah was there for further reparative surgeries for a congenital defect she had. A tube was sticking out of her neck to allow her to breathe. The doctor offered to do the operation pro-bono, but the hospital had no beds available for her.

I saw her father weep. I have already lost two daughters, he said, by settling to hospitals in the North because I couldn’t afford Beirut. I don’t want to lose her too. And in a corner of the room, I saw my colleague tear up.

Farah is 48% of the Lebanese population.

My colleague then approached me and said: this is something you need to write about, and so I did.