When a friend told me past midnight to check the news about Paris, I had no idea that I would be looking at a map of a city I love, delineating locations undergoing terrorist attacks simultaneously. I zoomed in on that map closer; one of the locations was right to where I had stayed when I was there in 2013, down that same boulevard.

The more I read, the higher the number of fatalities went. It was horrible; it was dehumanizing; it was utterly and irrevocably hopeless: 2015 was ending the way it started – with terrorists attacks occuring in Lebanon and France almost at the same time, in the same context of demented creatures spreading hate and fear and death wherever they went.

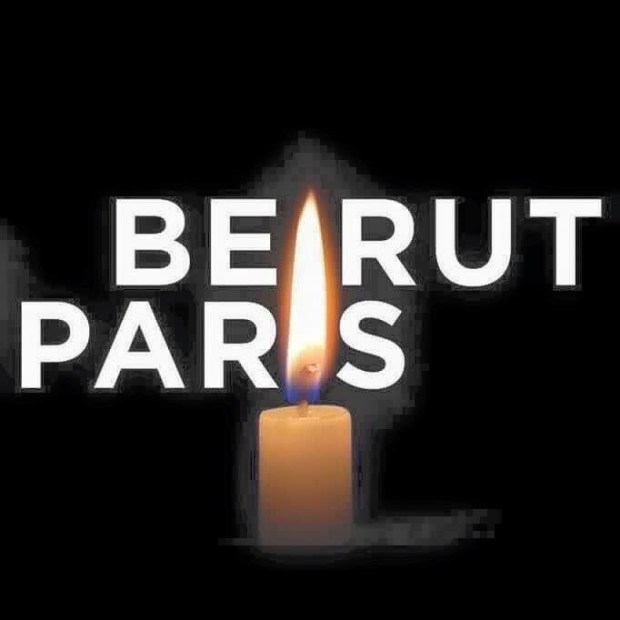

I woke up this morning to two broken cities. My friends in Paris who only yesterday were asking what was happening in Beirut were now on the opposite side of the line. Both our capitals were broken and scarred, old news to us perhaps but foreign territory to them.

Today, 128 innocent civilians in Paris are no longer with us. Yesterday, 45 innocent civilians in Beirut were no longer with us. The death tolls keep rising, but we never seem to learn.

Amid the chaos and tragedy of it all, one nagging thought wouldn’t leave my head. It’s the same thought that echoes inside my skull at every single one of these events, which are becoming sadly very recurrent: we don’t really matter.

When my people were blown to pieces on the streets of Beirut on November 12th, the headlines read: explosion in Hezbollah stronghold, as if delineating the political background of a heavily urban area somehow placed the terrorism in context.

When my people died on the streets of Beirut on November 12th, world leaders did not rise in condemnation. There were no statements expressing sympathy with the Lebanese people. There was no global outrage that innocent people whose only fault was being somewhere at the wrong place and time should never have to go that way or that their families should never be broken that way or that someone’s sect or political background should never be a hyphen before feeling horrified at how their corpses burned on cement. Obama did not issue a statement about how their death was a crime against humanity; after all what is humanity but a subjective term delineating the worth of the human being meant by it?

What happened instead was an American senator wannabe proclaiming how happy he was that my people died, that my country’s capital was being shattered, that innocents were losing their lives and that the casualties included people of all kinds of kinds.

When my people died, no country bothered to lit up its landmarks in the colors of their flag. Even Facebook didn’t bother with making sure my people were marked safe, trivial as it may be. So here’s your Facebook safety check: we’ve, as of now, survived all of Beirut’s terrorist attacks.

When my people died, they did not send the world in mourning. Their death was but an irrelevant fleck along the international news cycle, something that happens in those parts of the world.

And you know what, I’m fine with all of it. Over the past year or so, I’ve come to terms with being one of those whose lives don’t matter. I’ve come to accept it and live with it.

Expect the next few days to exhibit yet another rise of Islamophobia around the world. Expect pieces about how extremism has no religion and about how the members of ISIS are not true Muslims, and they sure are not, because no person with any inkling of morality would do such things. ISIS plans for Islamophobic backlashes so it can use the backlash to point its hellish finger and tell any susceptible mind that listens: look, they hate you.

And few are those who are able to rise above.

Expect the next few days to have Europe try and cope with a growing popular backlash against the refugees flowing into its lands, pointing its fingers at them and accusing them of causing the night of November 13th in Paris. If only Europe knew, though, that the night of November 13 in Paris has been every single night of the life of those refugees for the past two years. But sleepless nights only matter when your country can get the whole world to light up in its flag color.

The more horrifying part of the reaction to the Paris terrorist attacks, however, is that some Arabs and Lebanese were more saddened by what was taking place there than what took place yesterday or the day before in their own backyards. Even among my people, there is a sense that we are not as important, that our lives are not as worthy and that, even as little as it may be, we do not deserve to have our dead collectively mourned and prayed for.

It makes sense, perhaps, in the grand sense of a Lebanese population that’s more likely to visit Paris than Dahyeh to care more about the former than about the latter, but many of the people I know who are utterly devastated by the Parisian mayhem couldn’t give a rat’s ass about what took place at a location 15 minutes away from where they lived, to people they probably encountered one day as they walked down familiar streets.

We can ask for the world to think Beirut is as important as Paris, or for Facebook to add a “safety check” button for us to use daily, or for people to care about us. But the truth of the matter is, we are a people that doesn’t care about itself to begin. We call it habituation, but it’s really not. We call it the new normal, but if this normality then let it go to hell.

In the world that doesn’t care about Arab lives, Arabs lead the front lines.