Lebanese cinematic talent has not been given much room to grow. In a country where art is the least concern, cinema has found it especially hard to take off. However, a stream of Lebanese movies has been finding its way to our theaters. Some like Nadine Labaki’s previous movie, Caramel, were a huge hit with viewers. Others were not as lucky.

But the fact remains that the Lebanese audience is hungry for movies that describe its society, its problems, its worries and woes.

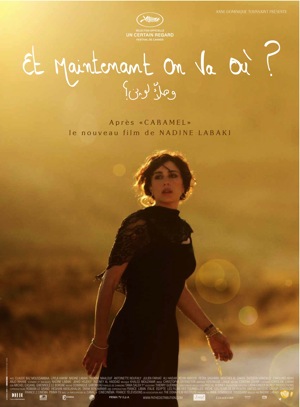

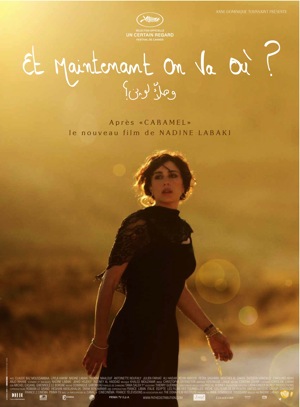

And then comes Nadine Labaki’s new movie: Where Do We Go Now, with its Lebanese title: W Halla2 La wein (also in French: Et Maintenant, On Va Ou?)

The premise of the movie is quite simple – and for many Lebanese, worry-inducing for fear of overuse of cliches. The overall basis of the plot is the coexistence of Lebanese Muslims and Christians in one community, sometimes peacefully and other times not. Many, like yours truly, felt the issue was overdone. Maybe not in cinema but in everyday life. Most of us are sick of being bombarded with commentary about the struggles that face our very diverse community. But this is not the case in Where Do We Go Now.

An unnamed village during the later part of the 20th century has its only connection with the outside world in the form of a very rudimentary bridge, around which landmines had been planted and never removed. Even TV reception is very poor to the village and the movie begins with a few youngsters searching for a broadcast signal to set up a TV night for the town-folks. This village is also a religiously divided community where the Church and the Mosque are only a house apart. And more often than not, the people live together happily.

But as it is, and despite barely having any access to news from the outside world, the men of this village start to confront each other in violent ways. Little things that would pass unnoticed cause them to explode, signaling the anger they’ve been bottling in. And it is then that the few women of the village start to devise plots to keep the men busy, entertained and get their minds off being violent. These plans will vary from fake miracles to putting hashish in cakes. But these women will go to every measure possible and break every limit imposed on them by society to keep their town together. And it is for these women, representing a vast majority of our Lebanese mothers, that this movie is so aptly dedicated.

Nadine Labaki, director of the movie and starring as Amal, is astonishing as always. You, really, cannot see her eyes on screen and not be mesmerized. She’s simply entrancing, even when she doesn’t speak. Then how about when she delivers a tour de force performance as one of those women, who happens to be in love with a man from the town’s other religion. But to be perfectly honest, the accolades one ought to give Labaki are not for her acting but for her directing. Never have I imagined a Lebanese movie can turn out this good and she makes it seem effortless. Her camera shots, her focus on details, her keen eye… all of this combine to give you a cinematic experience that will entrance you.

This movie, like Caramel, features mostly unknown faces and all of them deliver as well. It is hard to believe – and yet in retrospect so evident – that such acting can come out of common people that we all meet on the street. Where Do We Go Now is a movie of such epic proportions that these “unknown” actors and actresses (mostly actresses) deliver performances that are so subtly nuanced, so exquisitely flavored and so astonishingly well-done that they would put the best actresses and actors of Hollywood to shame. Yes, I have said it.

The score of the movie is chilling and haunting and wonderfully executed by Nadine’s husband Khaled Mouzanar. The movie also features a few highly intelligent songs, written by Tania Saleh.

And let’s talk about the script. What an ingenious way to tackle the subject at hand. Not only did Nadine Labaki not fall to any cliche known to us as a Lebanese community, but she managed to introduce them in a subtle comical way that would make us laugh at ourselves for uttering or doing them in the first place. The script is so strong it will turn you bipolar. Yes, lithium is advised to be taken at the door while going in. Why? Never have I laughed so hysterically one moment and just wanted to cry the other. And then after being utterly devastated, it brings you back to laughter. The movie plays with you like a ping pong ball. And you cannot but love every moment of it.

I was talking to my friend Elia the day before we went to watch Where Do We Go Now, which happened to be the day it won the People’s Choice Award at the Toronto Film Festival, and she said: “Elie, I’m very cautiously optimistic about this. I’m not letting my expectations overreach because I don’t want to be disappointed.” Well, I’m pretty sure Elia agrees with me on this: Where Do We Go Now brings out things in you that you didn’t even know you had. It brings out the best in you, as a Lebanese, sitting in that cinema chair for ninety minutes. And you need the best of the best to do that. Nadine Labaki, you deserve more than the few minutes of applause the people in the movie theater gave you. You deserve a full blown standing ovation. You have done the impossible. Again. Lebanese cinema has no excuse but to overreach for excellence now. And this movie deserves an Oscar win. Cheers to our mothers.